I am not one to impose my concept of beauty on others. Even so, I cannot help but be dismayed at the general decline in standards that has occurred over the past 50 years. The “cult of ugly” has descended upon us in seemingly every realm, be that fashion, art, architecture, work, or whatever. Most people seem to be far more concerned with whatever is trendy instead of what is actually beautiful. Does it really have to be this way?

I stand firmly against the cult of ugly, and I ask you to come with me to try to find true beauty in everyday life as well as in history, art, architecture, and other fields. Of course, we are all different: each of us has his or her own unique concept of beauty, and we each manifest it in our own ways.

This sensitivity and our perception are essential in assessing art, which is why I wanted to start our discussion by focusing on the definition of the common word beauty. It is a word that is very closely associated with the assessment of the world around us.

Where does this word come from and why is it so important?

The etymology of this word goes back to ancient Greece and the philosophical term kalokagatia - καλοκἀγαθία. This concept derived from the combination of two Greek expressions, καλὸς and κἀγαθός (kalos and kagathos) in a literal translation of beautiful and good.

For centuries, kalokagatia was a reflection of noble and ethical behavior. The first to use this word was Xenophon (Ξενοφῶν, Ksenophon, from Athens, born c. 430 BC – died c. 355 BC).

Greek writer, historian, soldier, and philosopher Aristotle ( Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotelēs, born 384 BC, died 322 BC), one of the greatest Greek philosophers along with Socrates and Plato, considered this formulation to be what he called a virtuous life, which very much had to do with doing actual good.

For all the Greeks of this period, the value of beauty and goodness were inextricably linked. In Christianity, beauty is also a quality of good but in a slightly different sense. Since the beginning of the modern age, good and beauty have been considered as two separate things, and this gave rise to ethics and aesthetics.

In a sort of evolutionary way, in consideration of ethics and aesthetics, the word happiness is commonly used to this day as a description of the highest good that man can achieve.

And how do we personally define beauty, whether our definition coincides with the definition of kalokagatia, καλοκἀγαθία.

Our definition of beauty and good is based on our life experience. Thus, we tend to say that good is not only what we like but also what we would like to have. Our desire to possess is directed, among other things, toward reciprocated love, honestly earned wealth, good food, or an eventful journey.

For good, we think about what awakens us. If we witness a heroic deed, we want to do the same kind of thing, do something that most of us consider to be truly great. However, if such an act brings suffering, sadness, or death, we become merely egoists. We nod our heads and claim that it is wonderful, but on the other hand, we do not want to have anything to do with it.

Our definition of beauty is hardly different. We add distance to our perception and then we do not arouse desire in ourselves, but only rejoice in it without consideration of our desire to have. These beautiful things please us no matter whom they belong to. Of course, I do not take into account the attitudes of people who are jealous, determined to possess things, and greedy because this type of desire does not make them beautiful.

Over the centuries, the perception of beauty depended largely on the spirit of the age. It has always changed and assumed different faces across countries and through time. The same epoch could represent beauty differently in literature and otherwise in painting or sculpture.

In closing our discussion of the definition of beauty and good, I invite you to the first comparative overview.

"The face and hairstyle of women as icons of beauty over the centuries."

What do you see? What do you consider beautiful?

Author unknown Antefix with a woman's head Department of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities: Etruscan Art (9th-1st centuries BC)

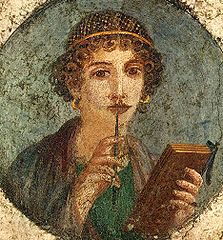

Author unknown Sappho, a fresco discovered in Pompeii https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safona

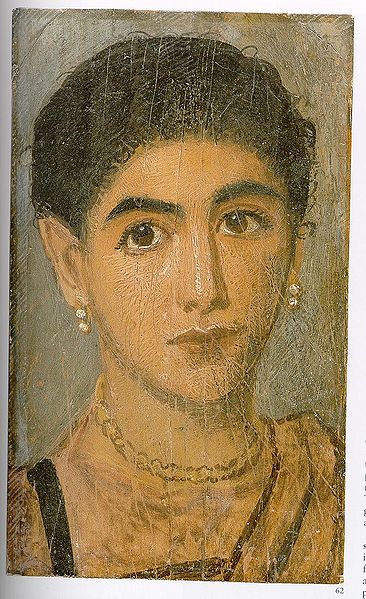

Author unknown Portrait of a Woman (1st-2nd centuries BC) Louvre Museum, Paris.

Author unknown Byzantine sculpture 540 AD The head of a woman is probably the face of Theodora. https://arteantica.milanocastello.it/en

Master of portraits of the Baroncielli, XV century Portrait of Maria Bonciani, Florence Gallery of Uffizi deghli https://www.epochs-of-fashion.com

Leonardo da Vinci Portrait of Lady with Ermine, 1488-1490, National Museum in Krakow https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dama_z_gronostajem

Titian Maria Magdalena, 1533-1535, Palazzo Pitti https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magdalena_(obraz_Tycjana)

Joshua Reynolds Miss Waldegrave, 1770, Edinburgh National Gallery of Scotland

George Romney Portrait of Lady Hamilton as Kirke 1782 London Tate Gallery

Marie Guillelmine Portrait of a Black Woman, 1800, Paris Louvre https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie-Guillemine_Benoist

Dant Gabriel Rossetti Lady Lilith, 1866-68, 1872-73 Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Lilith

Greta Garbo , 1932 photo by Clarence Sinclair Bull

Greta Garbo , 1932 Queen Christina

Audrey Hepburn 1954

I hope that I piqued your interest in at least looking at history and art in a slightly different way.

So much has changed over the centuries, and so little.

Next time, we will look at the very distant past, and we will consider what the aesthetic ideal of Ancient Greece was.

Bibliografia:

"Historia Piękna" wydanie pod redakcją Umberto Eco